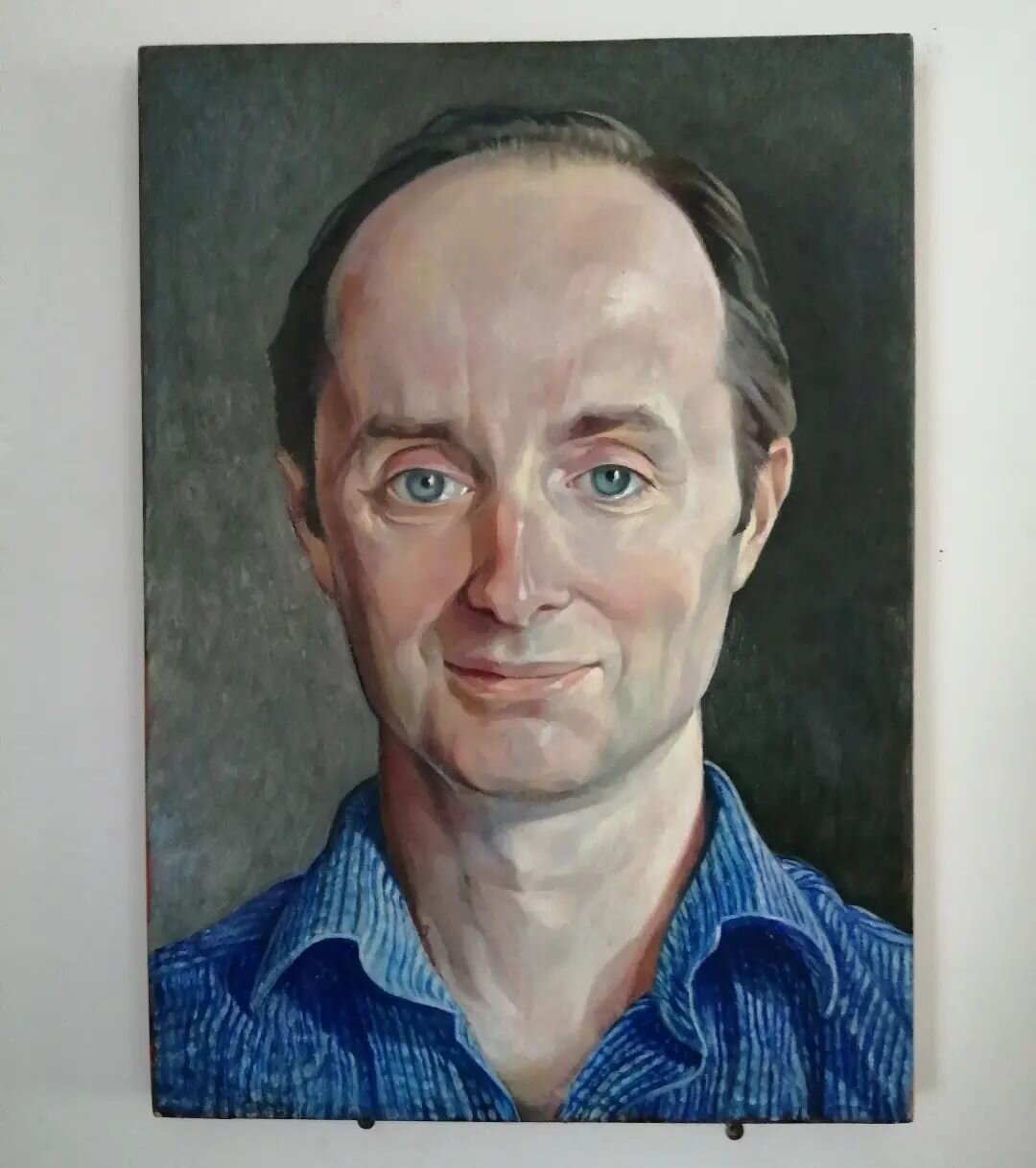

RONALD BLYTHE’s famous work Akenfield, published in 1969, along with later writings, had been a source of inspiration to me for some time. So, in 2008, I made a visit to the author, and he kindly let me draw and paint small studies of him for a show that I was preparing for that year in Dorset County Museum.

He was about 85 when I visited him at Bottengoms, the farmhouse on the Essex/Suffolk border which he inherited from his friend the painter John Nash. I found him gardening. Blythe smiled, shook my hand in silence, and led me inside for tea.

He was exactly true to his word(s) and everything I might have hoped: kind, generous, gentle, mercurial, sharp, witty, tremendously well read and learned, amused by the world, and deeply spiritual. As great people do, he showed me a level of hospitality and attention that I didn’t deserve. He made me feel as if I mattered, and he forgave my ignorance of so much that he knew and understood well.

It was one of those brief encounters of apparently small consequence which turn out to be quite profound, and I think of it still quite often.

He was extremely generous with his time, and showed me around the ancient farmhouse and garden, and local villages and their churches, besides sitting for me to draw him. He gently talked of artists and writers, of the landscape, and of aspects of Suffolk life, at one point springing upstairs to return with two walking sticks — one that had belonged to John Masefield, and the other that had been John Nash’s. Nash’s was topped with a black ball held in a bird’s claw.

Ronald had grown up with painters, knowing Cedric Morris and Arthur Lett-Haines, and had been part of the close circle of John and Christine Nash. He had, I think, a fascination with the processes of the painter — superficially very different from those of the writer, but containing the same creative core.

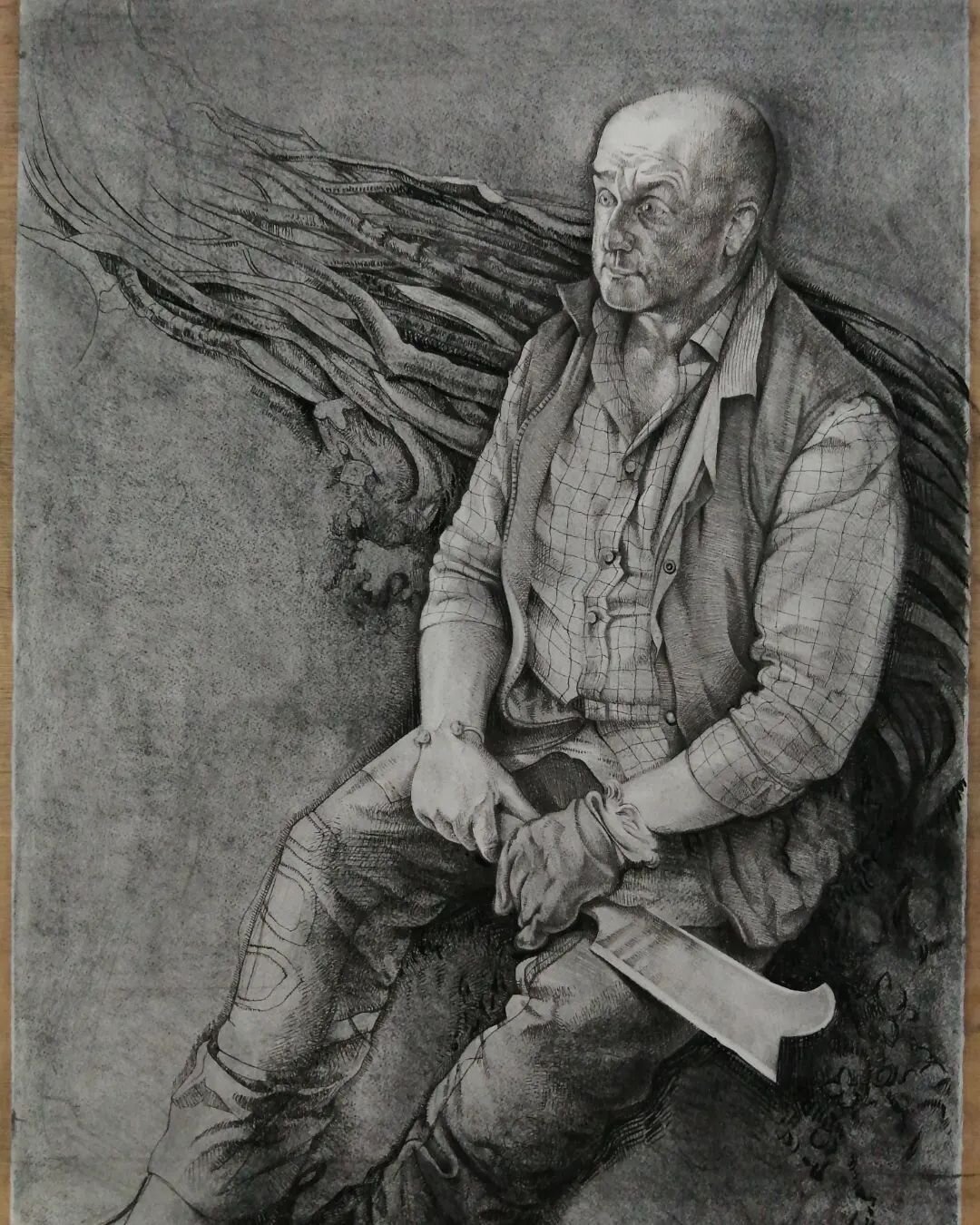

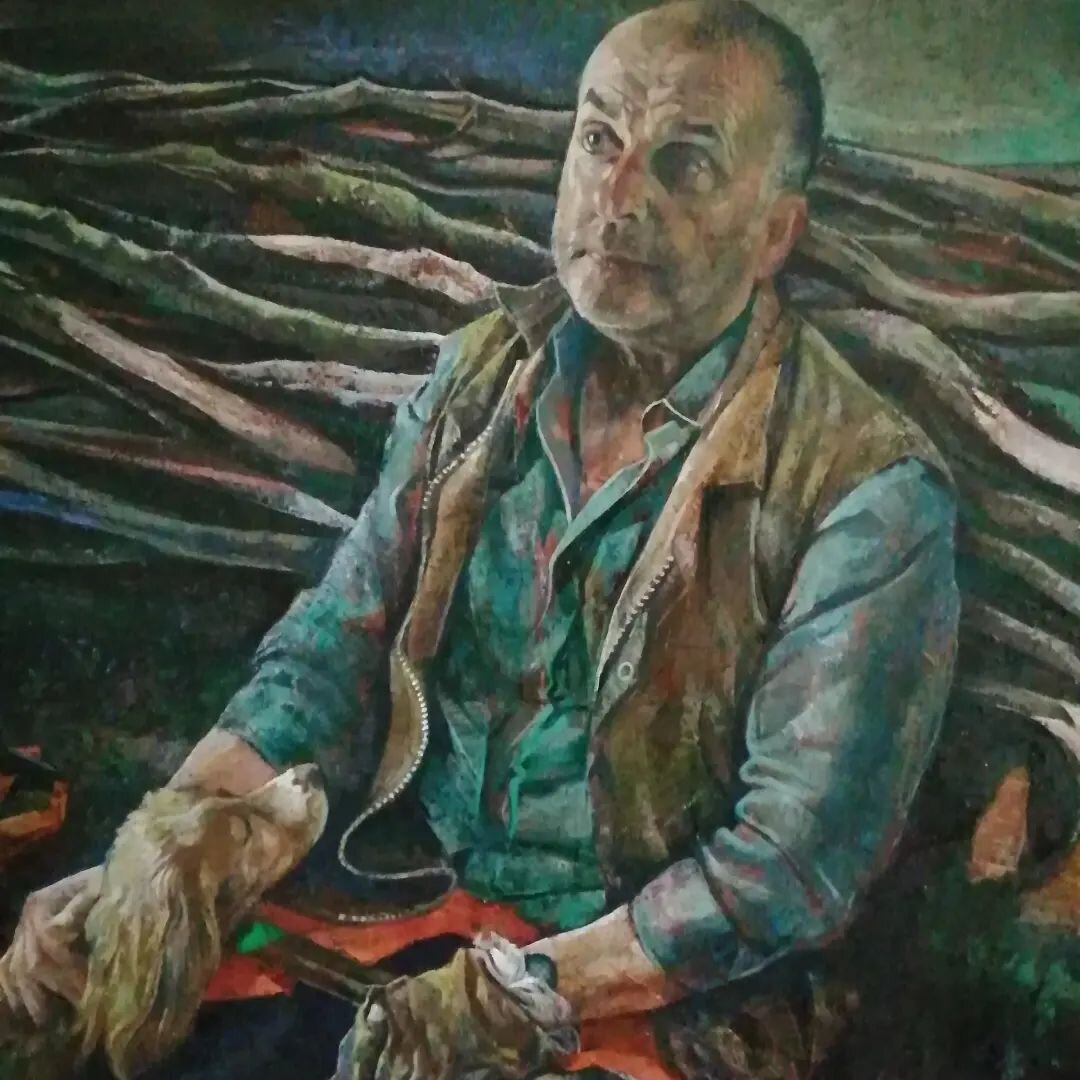

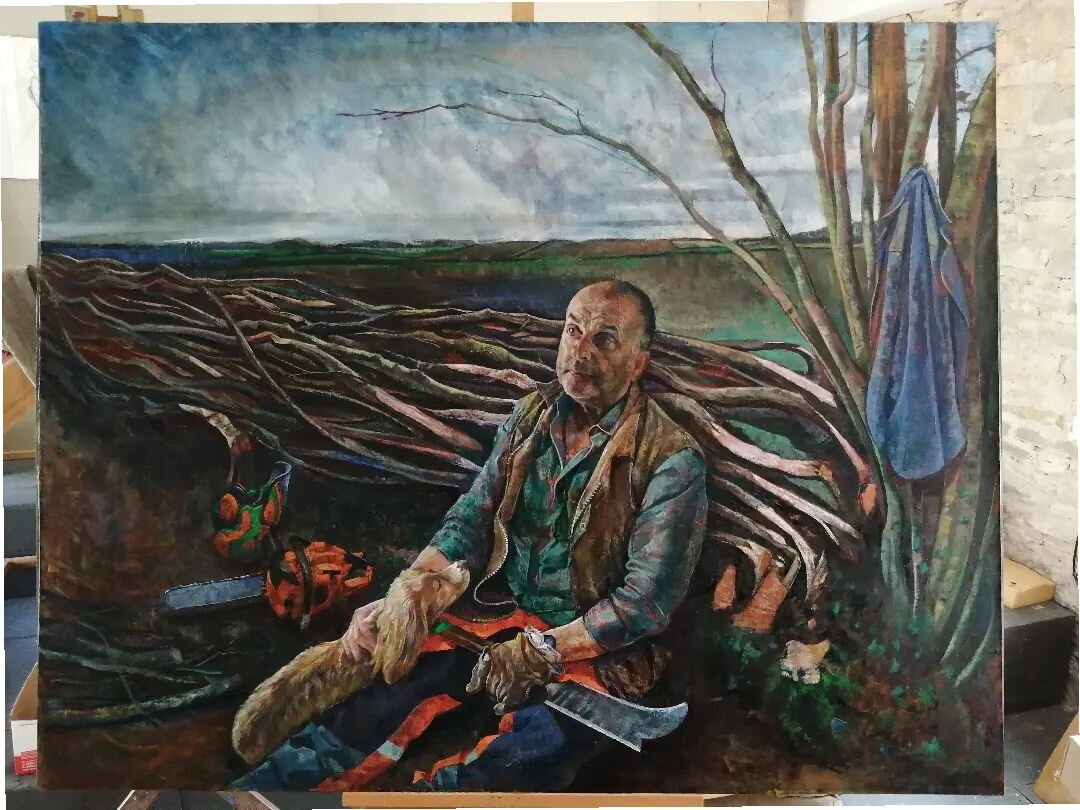

He spoke to me with great fondness about Nash, among many other friends of his. He gave me a dip pen from an old box full of the artist’s paraphernalia which he kept for occasions when painters might drop by — which they did. I used it when drawing a recent portrait of a Dorset hedgelayer. (The resultant painting was awarded The Ondaatje Prize for Portraiture this year at the Royal Society of Portrait Painters annual exhibition.)

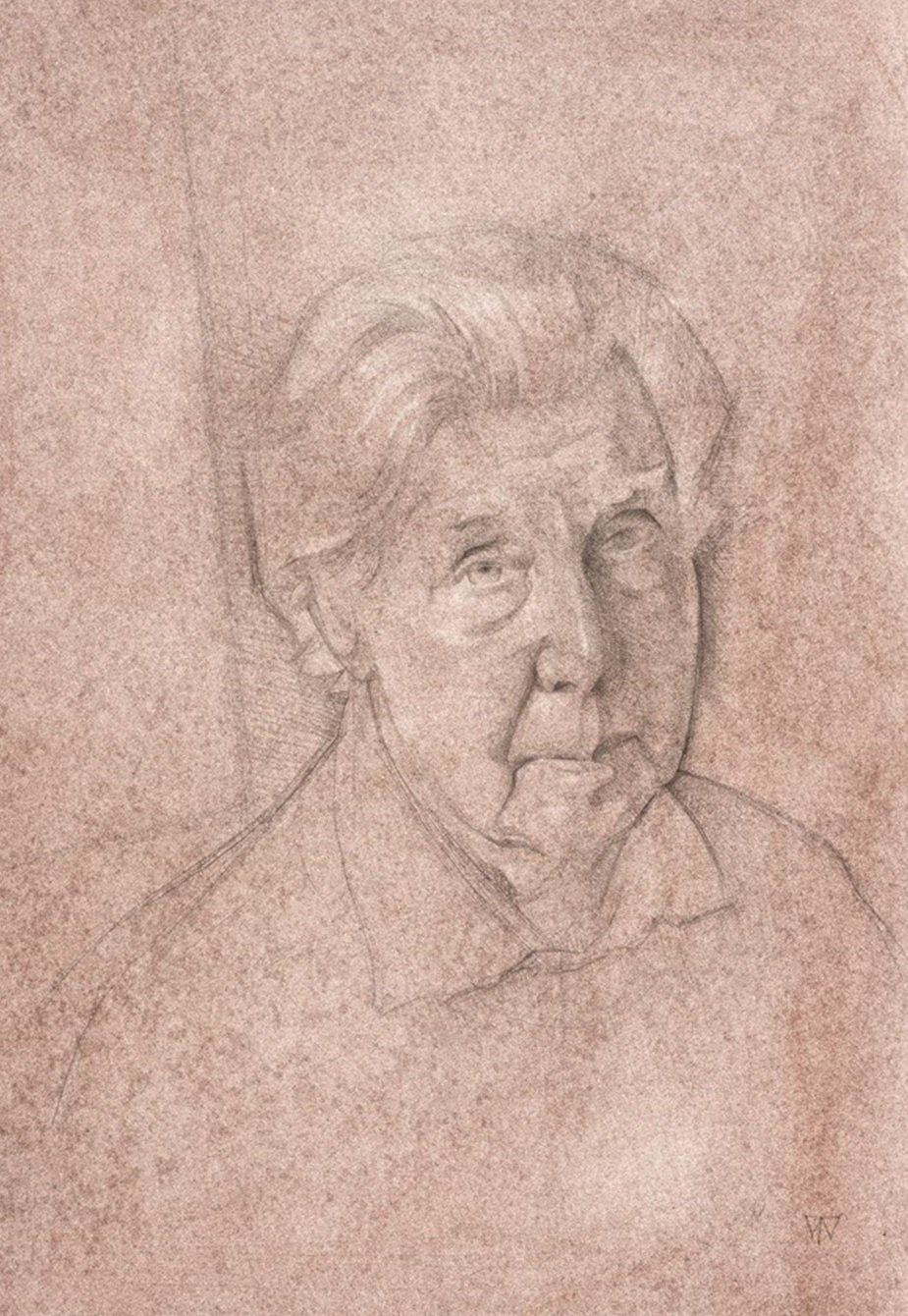

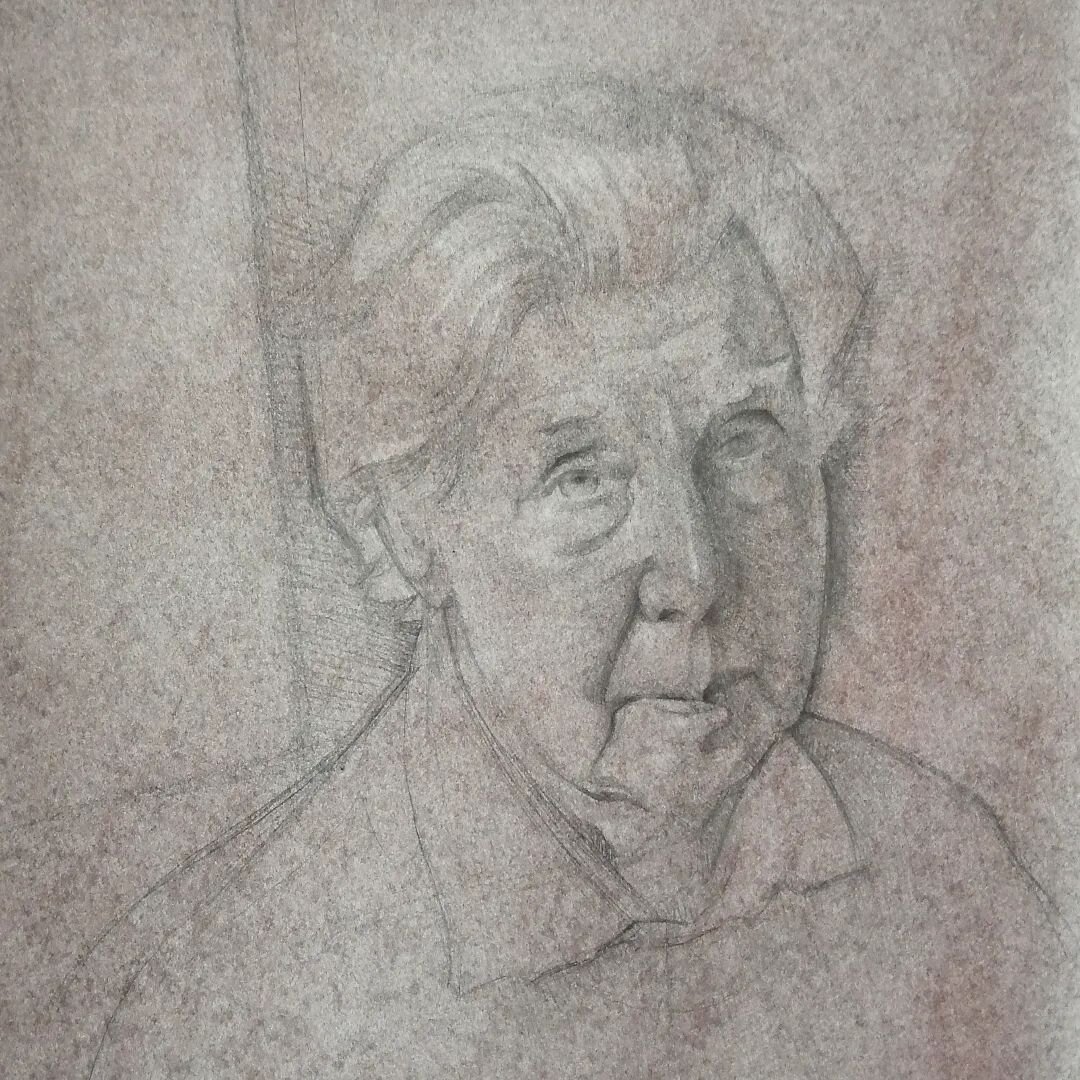

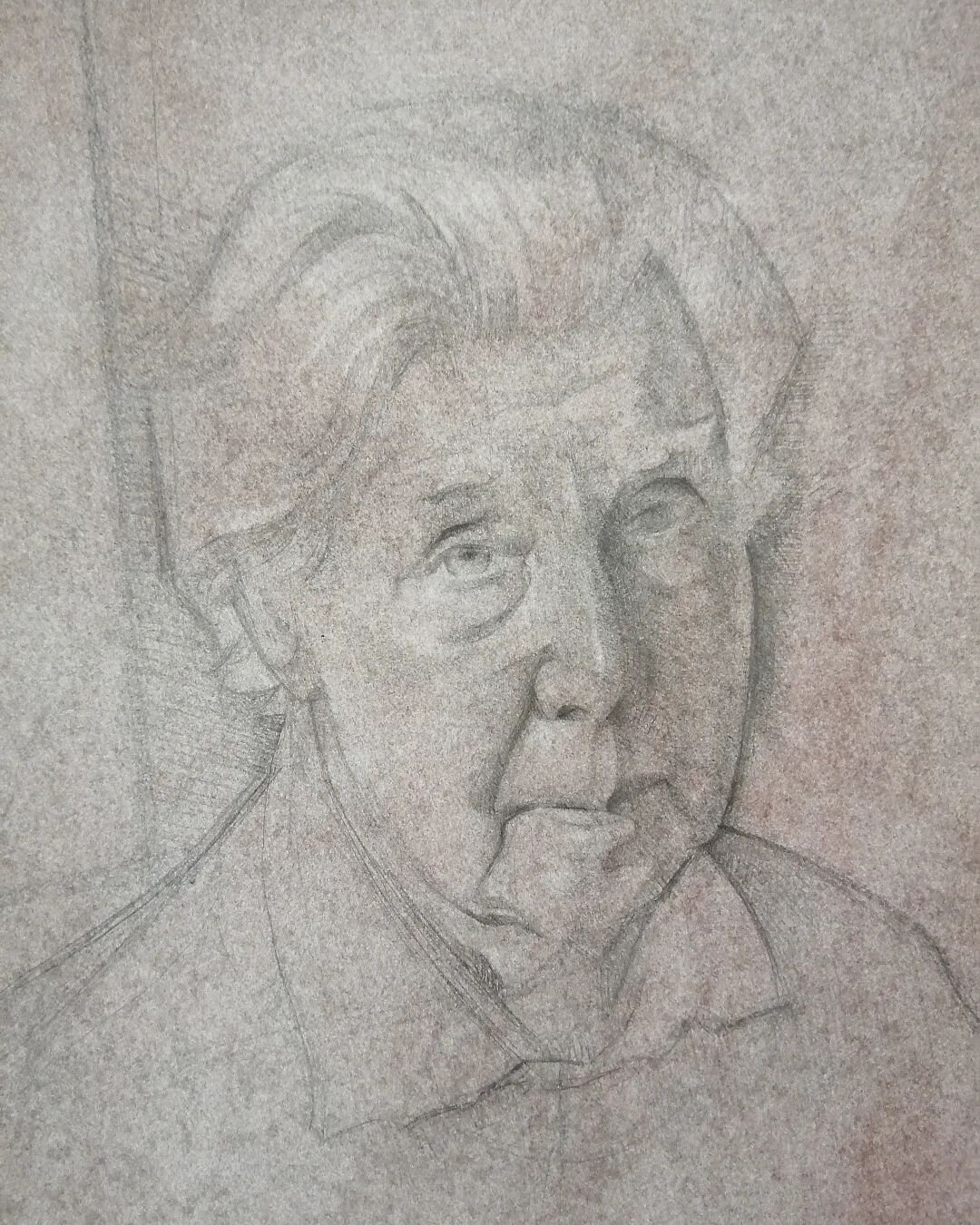

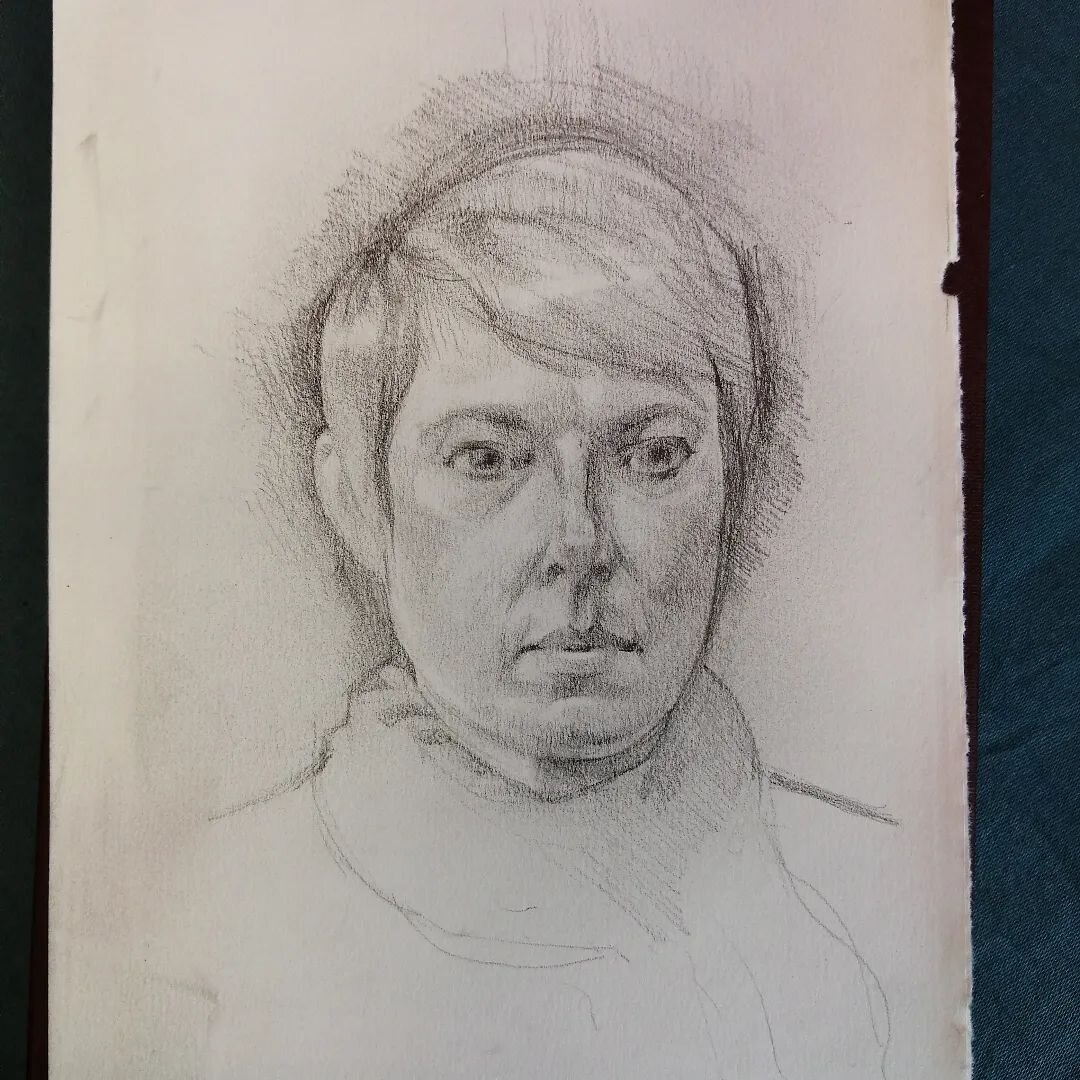

RONALD sat for me in his study at the top of the stairs, his back to a small, mullioned window overlooking the garden and illuminating his antiquated typewriter on the table at which he had continued to work for almost 40 years. Time was precious, he said, and you needed plenty of it to yourself for writing, as well as “just a few close and trusted friends”.

In a “Word from Wormingford”, in the Church Times, he wrote: “Not for us covetous desires and inordinate love of riches. Nor for us inordinate affection, although quite how one is to keep this within bounds I have failed to understand. Some friends, the cat, some books, this landscape familiar to me since boyhood, are all in receipt of my inordinate affection and the cat would not be pleased with anything less. But if I am not covetous, it is because I have all I need.”

I had intended to make a portrait of Ronald soon after my visit, but it just didn’t seem to happen. After hearing the news of his death (Obituary, 20 January) on the radio, I began to read his final publication, Next to Nature: A lifetime in the English countryside, (Books, 25 November 2022), having received it as a Christmas gift. I found, to my great surprise, that he had recorded my visit in one of the essays — a parting gift from this extraordinary man.

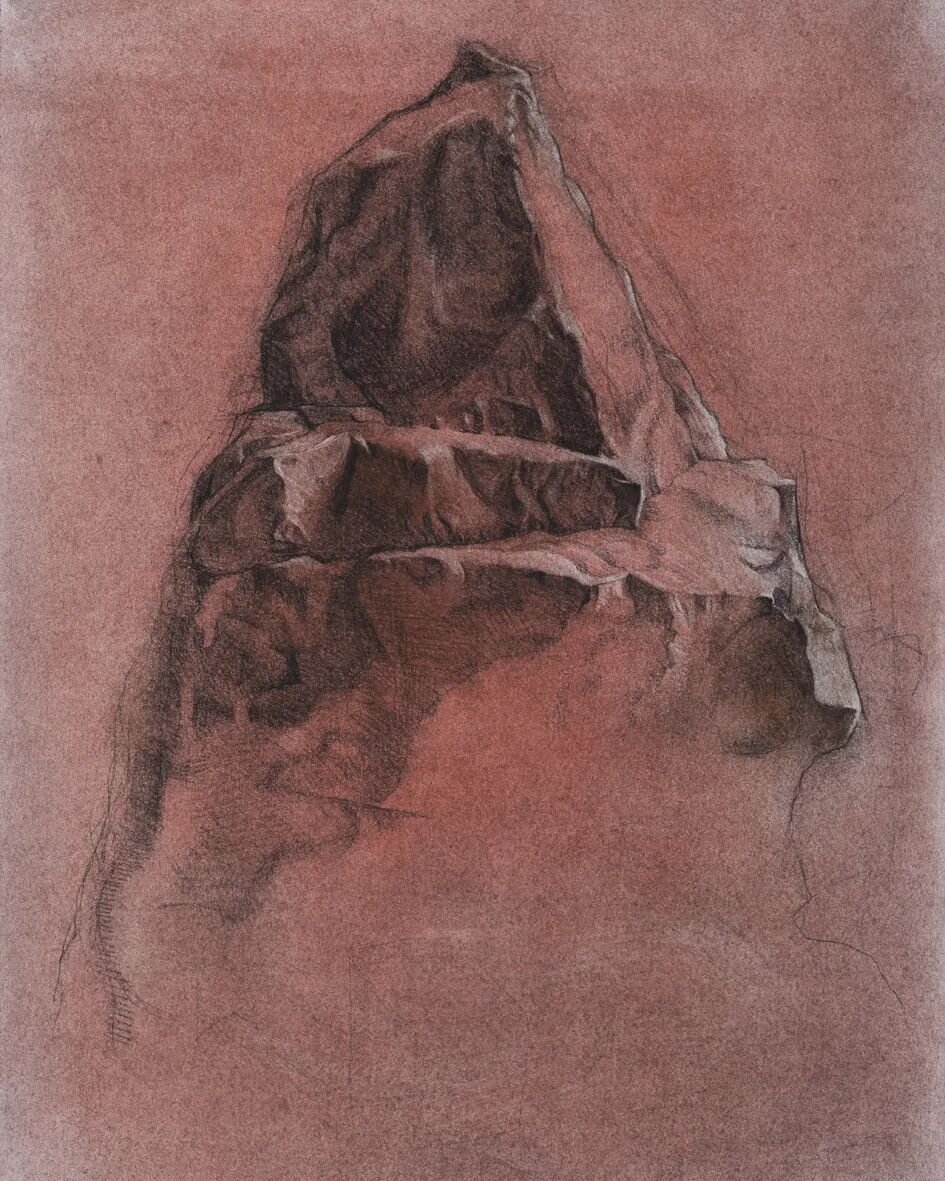

I have unearthed the sketches from 2008, and begin to work towards a painted portrait. I hope to exhibit this in 2024.

https://www.churchtimes.co.uk/articles/2023/9-june/features/features/the-cat-would-not-be-pleased-with-anything-less